December 12, 2022

Moshe Safdie Is Architecture’s Constant Gardener

Centuries after Aristotle described a profound human response to nature that he called biophilia, and decades before the design world would co-opt the term as a building ethos, a 13-year-old Moshe Safdie was tending bees on the roof of his family’s apartment in northern Israel and expecting he had a future in agriculture.

Safdie lived in Haifa, a tiered port city famous for its lush terraced gardens. When he was born in 1938, Haifa was in Palestine, but the world convulsed and changed during his childhood, and like many teenagers in a young Israel, Safdie assumed that after his years of required military service he’d live an agrarian lifestyle as part of a kibbutz. It wasn’t to be. Instead, his parents, worried about the volatile politics, decided to migrate to Canada, where they had some family. And so Safdie had to give up his bees and his garden city for frigid Montreal in March.

“There was snow on the ground, but the seasons were changing just enough to add an element of slow melting to the equation, and everything left by dogs in the previous three months had combined with the mud and the trash left by human beings to turn the streets and sidewalks into a slippery soup,” he writes in his poetic new memoir If Walls Could Speak (Grove Atlantic, 2022). “I was in a state of total shock.”

As my Uber pulled up to the headquarters of Safdie Architects in Somerville, Massachusetts, on a verdant late-summer morning this year, my driver turned around and said, “What is that?” The simple brick structure, formerly a factory, was enshrouded in ivy, trimmed only enough to reveal doors and windows. The receptionist said the building surprised her at first too: “It’s like a Chia Pet.”

A trim and agile 84-year-old Moshe Safdie appeared, mustached as always, and led the way upstairs to his studio office, where he opened the casement windows to show me honeybees at work in the blossoming ivy. He reached his arm out among dozens of them—no fear, no stings. Turns out they’re local. He keeps two hives on the roof.

Safdie’s office table was covered with sketches and renderings of megaprojects, the scale he’s come to be known for. Some were in process, some still dreams, but all surprisingly green. We sat down together to trace the through line of biophilia in his decades of work, even though he has no use for the term.

“When I was asked about biophilia in the ’80s, I said, ‘That’s what I’ve been doing my whole career,’ ” Safdie said, chuckling at first and then turning serious. “The conviction that plant life must be always integrated into architecture no matter how urban and dense was a very early conclusion.”

It started for him in the middle of the past century. Following that rough introduction to the Montreal climate, Safdie threw himself into academics for the first time in his life. A high school aptitude test decreed him suitable for architecture, and he decided to pursue it at McGill University. By his fifth year, he proved far more than suitable and was chosen for a travel scholarship touring housing projects and complexes around North America. One of the places he stopped was a freshly built Levittown.

“I wrote in a report when I got back that I wouldn’t want to be caught dead there,” he remembers. “Boredom, isolation, the commitment to commuting. But they obviously preferred that because they had a garden and a house, and therefore the conclusion: Can we do that in an urban context?”

He set out to try. His thesis project was a grand modular housing system—more like a planned city—that had as one of its objectives “For Everyone a Garden.” He cantilevered stacks of rectangles LEGO-style, placing garden terraces on the edges that jutted out high off the ground. The idea was so visionary, it not only secured him a job with Louis Kahn in 1962, but shortly after, it was chosen as a key element of the upcoming World Expo in Montreal. Not all of his thesis was built, but the part that did come to life as Habitat 67 reverberated well outside the world of design, even landing Safdie on the cover of Newsweek.

Within the industry, meanwhile, Safdie’s sky-gardening and “density with dignity” ideas took some hits. “The criticism was like, ‘Utopian and not achievable on any scale,’ ‘It’s too precious’ or ‘too difficult’ or ‘too expensive,’ ” Safdie says. And so began some difficult years (decades of them, to be frank), when he sent out proposal after proposal for visionary projects around the globe, only to have them ignored, rejected, or chucked at the last minute by recessions and politics.

Still, the lean years for Safdie’s reputation were by no means barren. He was getting commissions and slowly developing his palette, prioritizing natural elements as much as brick and steel. The examples are myriad: a round chapel on Harvard’s campus intersected by a glass triangle framing a fragrant “biblical plants” garden with seats in a fish pond; a federal courthouse wrapped around and illuminating two old-growth trees Safdie refused to cut down; a water-enveloped Arkansas art museum, Crystal Bridges, featuring laminated beams of local yellow pine; a new building for Israel’s Holocaust History Museum, Yad Vashem, where he designed a long triangular prism that penetrated a mountain peak, moving visitors toward a light-filled precipice.

Safdie had grown accustomed to working outside the industry zeitgeist in those years. He not only eschewed Postmodernism but publicly attacked it for a lack of humility and service to humanity. (Not a lot of party invites back then.) But just as he was passing through middle age, the industry began awakening to environmental degradation, ushered in by energy crises and scientific warnings about the limits of natural materials once considered unlimited. A “green revolution” had caught up to Safdie’s steady evolution, sweeping architecture into an era of critical thinking about all those steel-and-glass towers with inoperable windows. The marketplace was at last fertile for Safdie’s gardens.

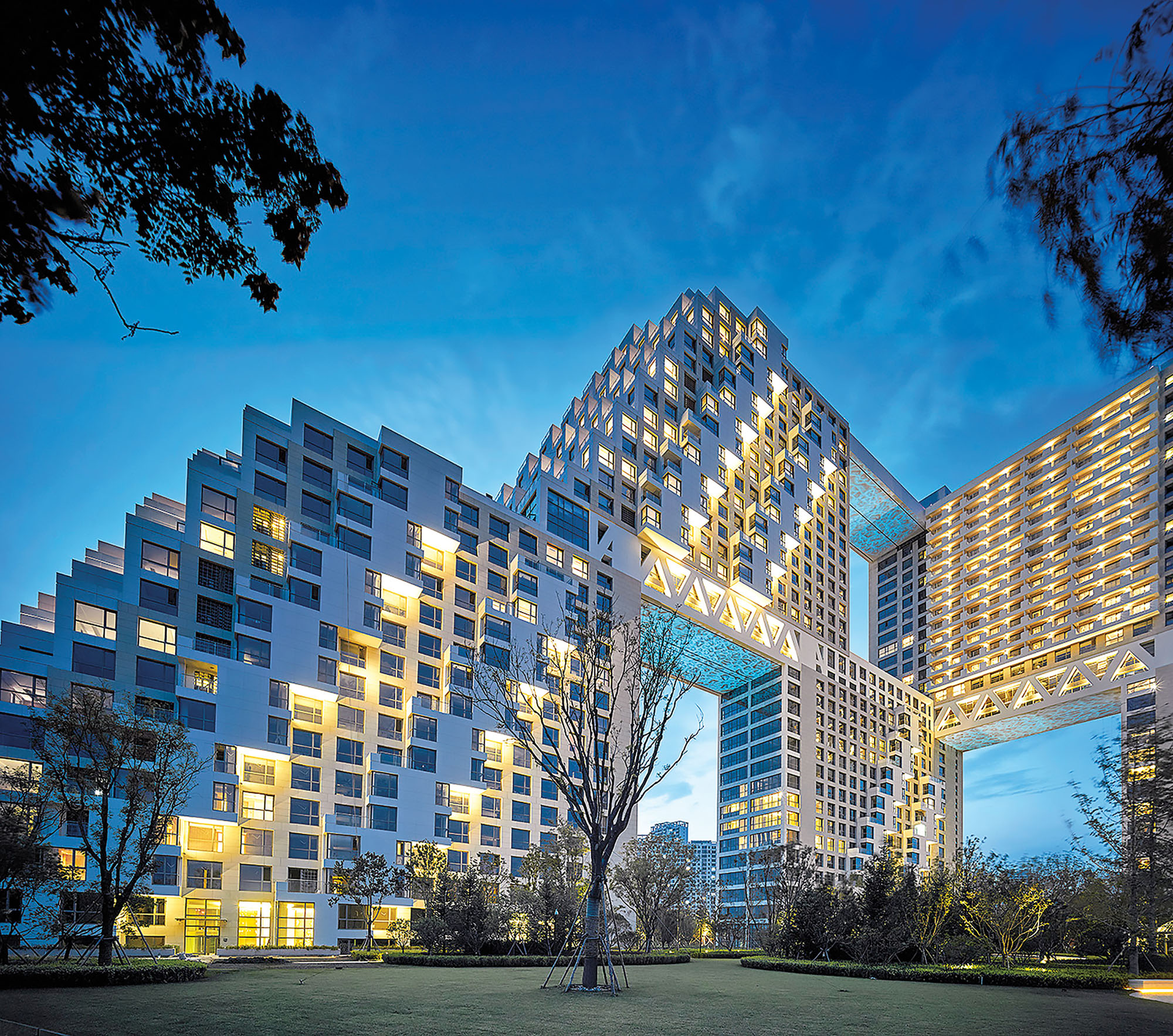

His response was mega, to say the least. In the past 15 years, Safdie Architects has completed Habitat-like multiuse complexes—staggered structures complete with green roofs and terraces—much larger and denser than in ’67, including Sky Habitat in Singapore, Habitat Qinhuangdao in China, and Altair Residences in Sri Lanka, with more on the way. Also in Singapore, they built one of the world’s most distinctive and expensive sky parks with 2.5 acres of trees (chosen for their ability to withstand extreme heat and wind), a jogging path, a public observation deck, gardens, restaurants, and an infinity edge pool cantilevered atop the three 55-story hotel towers of the Marina Bay Sands casino resort. They designed another sky-high tower-connecting park (this one covered) in a major mixed-use development set at the confluence of two rivers in Chongqing, China: Raffles City.

But most famously to date, Safdie turned a Singapore airport into a nearly indescribable indoor paradise garden most people now just call “Jewel.” Working with a sprawling team that included PWP landscape architects and Buro Happold engineers, Safdie’s team designed a five-story, terraced tropical garden (featuring more than 2,500 trees and 100,000 shrubs from around the world) encircling the planet’s tallest indoor waterfall, a vortex of recycled rainwater free-falling at a rate of 10,000 gallons per minute. Photographs of Jewel Changi Airport look almost fake—it’s like a biophilia fantasy-rendering come to life. Jaron Lubin, a senior partner at Safdie Architects, got married there during the week of its grand opening.

Jewel has opened doors for Safdie and sparked his imagination. His teams of engineers and landscape architects are evolving new ways of building maintenance systems for plant life, providing humidity, leaf washing (dusty leaves attract mites and prevent photosynthesis), and the right amounts of light and water. Those innovations have allowed Safdie to dream bigger, knowing that his indoor parks especially can stay alive. He worked with Isabel Duprat Landscape Architecture in Brazil to create elaborate garden courtyards of native flora for the Albert Einstein Education and Research Center in São Paulo, Brazil. And for the Serena del Mar Hospital in Cartagena, Colombia, Safdie planted a full bamboo forest along the spine of the sprawling facility, offering both patients and staff mental respite—biophilic design has been proven in multiple studies to speed healing—and a lush way to navigate from wing to wing. Habitat Qinhuangdao is about to be expanded, as are Crystal Bridges and Marina Bay Sands.

He says that his upcoming projects integrate so much plant life that they’re like “Jewel on steroids.”

Still, though highly lauded and people-pleasing, none of Safdie’s recent victory-lap projects have been low-carbon ventures. He is adamant about refusing to greenwash anything. As Lubin puts it: “Construction is by definition extremely damaging to the environment. We like to talk about resilience and timelessness.” Indeed, nowhere in Safdie’s more-than-350-page memoir does he ever mention climate change, global warming, or carbon emissions. “I made that choice,” Safdie says. “I find the term ‘sustainability’ is abused and has become a marketing device.” In this area, the industry zeitgeist may be moving out of sync with him again, prioritizing quantitative measures of climate mitigation even at mega-scale, but he stands by his long-held principle that “responsible design” evolves—he believes that in the next 50 years, new materials and energy sources will help move architecture past fossil-fueled habits.

At the end of his book, Safdie includes a poem he wrote four decades ago in Jerusalem, a distillation of his beliefs. Arrogance is incompatible with nature, it reads in part. When I asked him about that line, he said we’re seeing it now…the arrogance of building in a flood plain, the arrogance of pushing nature too far and losing too many species. “I’m also of the disposition that we surprise ourselves in coming up with solutions,” he says. He has just purchased an electric car. Each morning before work, he tries to go for a swim, and when it’s warm enough, he drives to nearby Concord to swim in Walden Pond.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

5 Buildings that Pushed Sustainable Design Forward in 2022

These schools and office buildings raised the bar for low-carbon design, employing strategies such as mass-timber construction, passive ventilation, and onsite renewable energy generation.

Projects

The Royal Park Canvas Hotel Pushes the Limits of Mass Timber

Mitsubishi Jisho Design has introduced a hybrid concrete and timber hotel to downtown Hokkaido.

Profiles

Meet the 4 New Design Talents Who Made a Mark This Year

From product design to landscape architecture and everything in between, these were the up-and-coming design practices making a splash in 2022.