October 20, 2021

David Benjamin’s Venice Biennale Installation Makes the Case for Probiotic Living

The architect and his team want to translate this fundamental understanding into how we build structures in the future, especially when it comes to ensuring a level of symbiosis and interspecific cohabitation. At the core of Benjamin’s proposal are porous environments that can host both humans and microbes, with the latter serving as a natural form of HVAC. “A holobiont is a collection of different species living together, each contributing to the well-being of the whole,” Benjamin explains. “If we think of buildings in this way, we might design for more than just human comfort. This gives us a new perspective on life and health.”

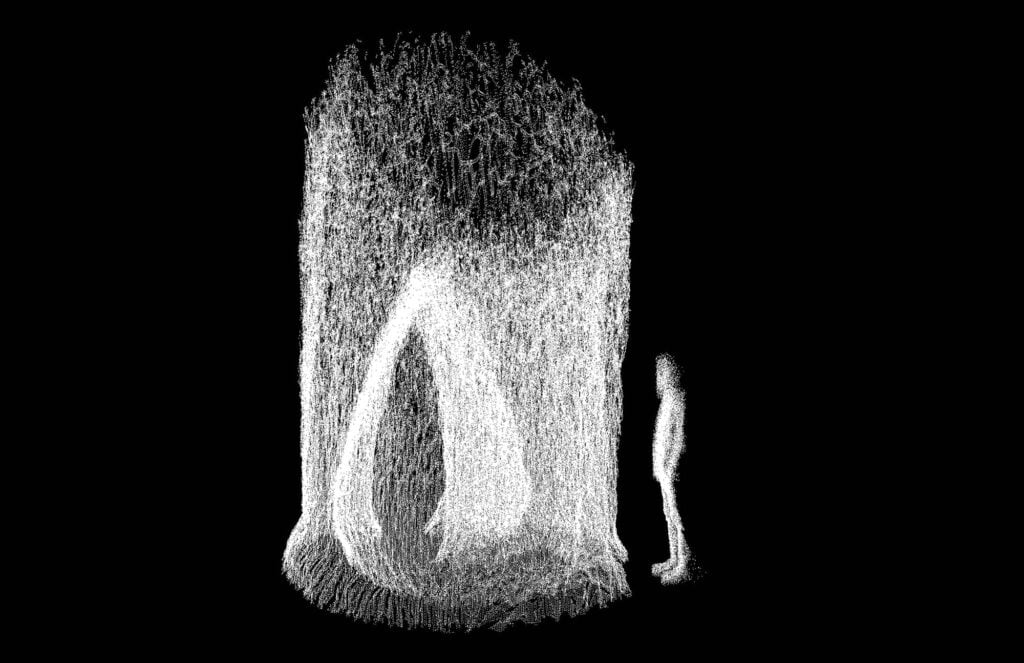

As demonstrated by the various mock-ups on view as part of the “Alive” installation, nontraditional bio-receptive materials like dried fibers of luffa might offer viable alternatives to the sleek, sterile, and industrially produced materials we’re accustomed to. Such plant-based substitutes are inexpensive, low-carbon, renewable, and fast-growing. Taking on aesthetic and structural qualities all their own, these experimental substances also accommodate different light and airflow zones.

“The project is a prototype for the architecture of the future. Recent advances in biological technologies—combining artificial and natural intelligence—can supercharge our creativity and also help address complex problems like climate change and inequality,” the architect concludes. “At the same time, this is also relevant to current buildings. A sustainable material like a luffa can be used in many environments: partition walls, acoustic-tiled ceilings, or even microbial facades that remove pathogens from the air.”

On the other end of the spectrum experts from Gensler and Columbia University Irving Medical Center lay out a blueprint that seeks to protect us from pathogens, arguing that we must implement strategies and standards for infection control in all spaces to prepare for the future. Read the full story here.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

5 Buildings that Pushed Sustainable Design Forward in 2022

These schools and office buildings raised the bar for low-carbon design, employing strategies such as mass-timber construction, passive ventilation, and onsite renewable energy generation.

Projects

The Royal Park Canvas Hotel Pushes the Limits of Mass Timber

Mitsubishi Jisho Design has introduced a hybrid concrete and timber hotel to downtown Hokkaido.

Profiles

Meet the 4 New Design Talents Who Made a Mark This Year

From product design to landscape architecture and everything in between, these were the up-and-coming design practices making a splash in 2022.