February 23, 2021

Form Follows Fantasy: The Rise of the “Dreamscapes” Movement

If there is any place to play around with trends, it’s in the digital universe, where things won’t be sent to a landfill as soon as they are out of fashion.

But rather than aiming to achieve a believable likeness, an emerging group of artists and designers are experimenting with architectural representation and computer-generated imagery to critically explore the surreal. The result is images that blend fiction and reality while probing the extent of our escapism.

Last year Berlin-based publisher Gestalten released a survey of this new aesthetic movement, titled Dreamscapes & Artificial Architecture: Imagined Interior Design in Digital Art. Framing the trend as expressing the “impossible” architecture of dreams, the volume presents the images as utopian spaces we visit when we are asleep or lost in thought. Notably, dreamscapes are not meant to be built, but rather to stretch the limits of our perceptions of interior space.

Composed of work by over 40 artists, the book highlights that such software is no longer industry specific: “You don’t have to be an architect to design a building, or an interior designer to render a space.” Designers of these virtual spaces are sometimes formally trained in architecture or interior design, but many also come from a variety of backgrounds including game design, motion design, and advertising.

While the book is meant to pose more questions than answers, some remain unasked: Who is the audience for these “dreamscapes?” Who is the dreamer, the creator, or the spectator? And how can our interior fantasies turn into a stage set for e-commerce?

The movement is inextricable from social media. The glossy textures and cinematic lighting achieved through rendering software are best viewed on a screen—brightness turned up. When you’re viewing the images on Instagram, the content fosters a sort of hyperreal spatial ASMR that can spark feelings of euphoria and a brief sense of relief amid the endless scroll. Some transport you to a peaceful vacationland, while others become more unsettling the longer you look: Take, for example, self-described “ludicrous architecture studio” Zyva Studio’s dystopic apartment filled with oversize pills and anime-inspired furniture. Many of these artists have garnered substantial followings, including London-based interior designer and creative director Charlotte Taylor, who has surpassed 200,000 followers for her collaborative 3D work with other digital creators.

If these are the spaces of dreams, then their designers are the lucid dreamers.

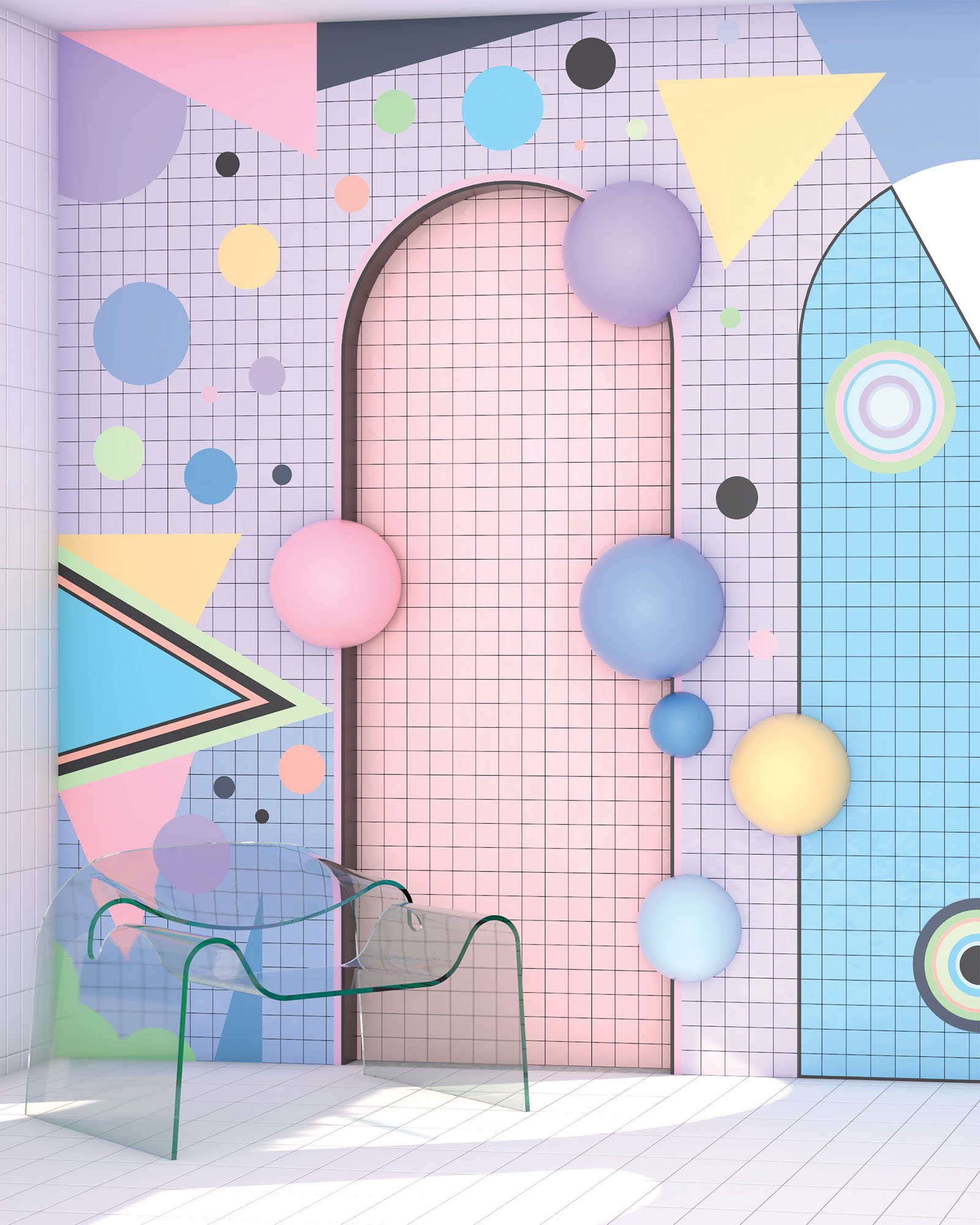

With the power to visualize any space, what can we learn about the social impact of taste from the object and material choices? Imagined interiors are often depictions of the artist’s nostalgia, as is the case with Ana de Santos Díaz’s Postmodern pastel paradises or Thomas Dreux’s AstroTurf-covered room intended for listening to ’90s hip-hop and R&B records. The scenes also transfer viewers to worlds that create pastiches of art and design movements across time—in this new digital universe, it’s not uncommon to find allusions to René Magritte alongside an adobe-style home decorated with Henri Matisse paintings and Faye Toogood furniture. Some tropes recur throughout the portfolios of dozens of creators across the globe, blurring the lines between the visionary and the trending.

Many of these imagined worlds’ material choices reflect an ironic self-awareness of digital space as well as an intention to show off the strengths of the medium. In this realm, designers can specify the wildest luxuries or even use plastics guilt-free because environmental crises don’t exist here. For Australian artist Nicole Wu, this can look like covering an entire floor in sand or even drawing down the moon so that it rests gently at your feet. Tiling a whole room is just a texture map away If there is any place to play around with trends, it’s in the digital universe, where things won’t be sent to a landfill as soon as they are out of fashion.

Of course, this freedom of representation has ample advantages when it comes to advertising. In lieu of physically visiting stores, one can browse and virtually experience products in unconventional locations. Such is the case with Ariel Palanzone’s whimsical stills of quilts designed by Studio Proba and Victor Roussel’s depiction of ceramicist BZIPPY’s architectural planters and side tables. Amid COVID-19, such scenes helped replace canceled fairs and shows with digital exhibition spaces, including Sight Unseen’s annual Offsite event and Anna Broeng’s rendering of an “imaginary” exhibition for furniture designer Gustaf Westman.

To be sure, these computer-rendered interiors are more contrived than the confusing, fragmented landscapes of our unconscious. If these are the spaces of dreams, then their designers are the lucid dreamers. The scenes encourage viewers to reexamine the emotional role of interior design and provide a glimpse into how the built environment affects the psyche. Perhaps 3D-modeling software not only paves the way for new methodologies in social media marketing but also serves as a liberating tool for imagining new worlds.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

5 Buildings that Pushed Sustainable Design Forward in 2022

These schools and office buildings raised the bar for low-carbon design, employing strategies such as mass-timber construction, passive ventilation, and onsite renewable energy generation.

Projects

The Royal Park Canvas Hotel Pushes the Limits of Mass Timber

Mitsubishi Jisho Design has introduced a hybrid concrete and timber hotel to downtown Hokkaido.

Profiles

Meet the 4 New Design Talents Who Made a Mark This Year

From product design to landscape architecture and everything in between, these were the up-and-coming design practices making a splash in 2022.