June 18, 2021

Can Craft Save America?

A trio of exhibitions seeks to rediscover something about our nation through the work of its makers and artists.

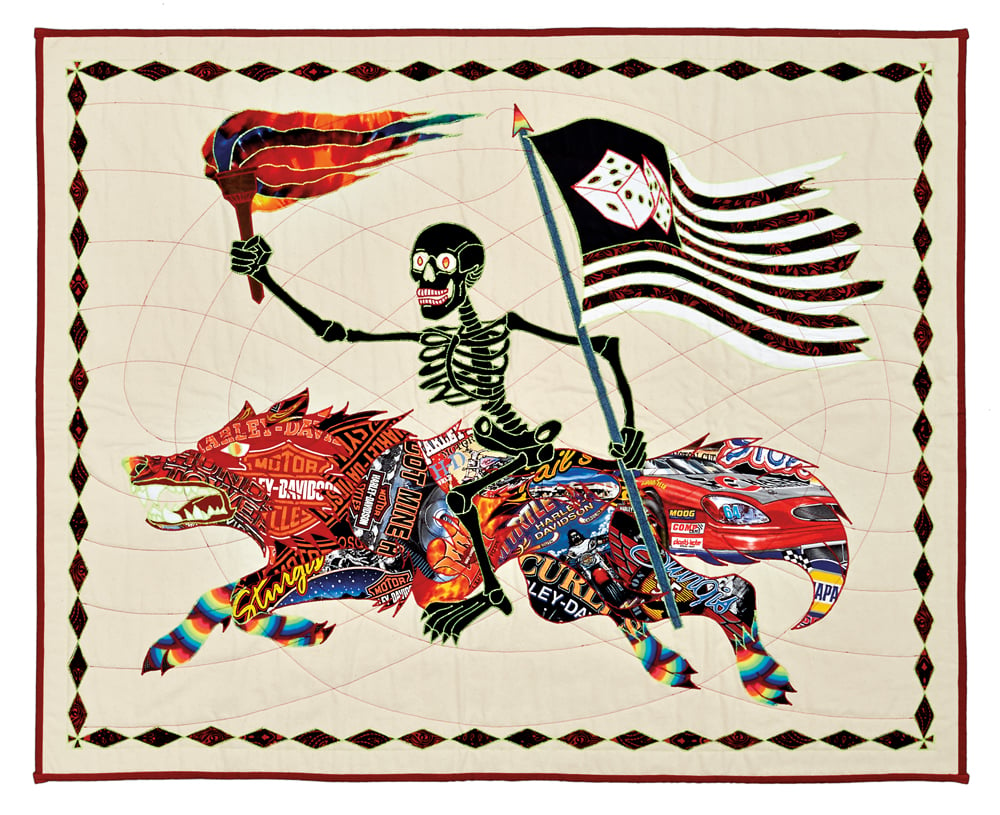

Venom explores the political history of quilt making in I Am the Night Rider, a handmade quilt crafted out of recycled fabric. By pulling from subcultural movements like punk rock, heavy metal, and biker gangs, the quilt is said to function as “an allegory of present-day America.” Courtesy of the Gregg Museum of Art & Design

During the first residency of the critical craft studies graduate program I direct at North Carolina’s Warren Wilson College, our students and faculty asked, “Can craft save America?” This was also one of the 100 questions asked in a 2018 workshop led by Lisa Jarrett and remains top of mind as I think about a trio of exhibitions that connect craft and nationhood in these troubling times: R & Company’s Objects: USA 2020, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art’s Crafting America, and the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019.

All three signal a new interest in the connection between craft and national identity; however, given curator and independent scholar Glenn Adamson’s engagement with the first two, in addition to his recently published book, Craft: An American History, this may be more about curatorial coincidence than the zeitgeist. Regardless, making through craft and making a nation go hand in hand, and the instrumentalization of craft to “Save America” is not new.

Nearly every decade in the past 50 years has included a large traveling exhibition surveying craft and its connection with national identity. In 2007, it was Craft in America: Expanding Traditions, created by Craft in America, a Los Angeles–based organization best known today for its award-winning PBS series. The exhibition was selected to launch the reopening of Portland, Oregon’s Museum of Contemporary Craft (MoCC) in 2007, with the idea that it could provide visitors with a foundation for conceptualizing the Studio Craft movement in the United States, and act as a springboard for new approaches to curating craft for staff.

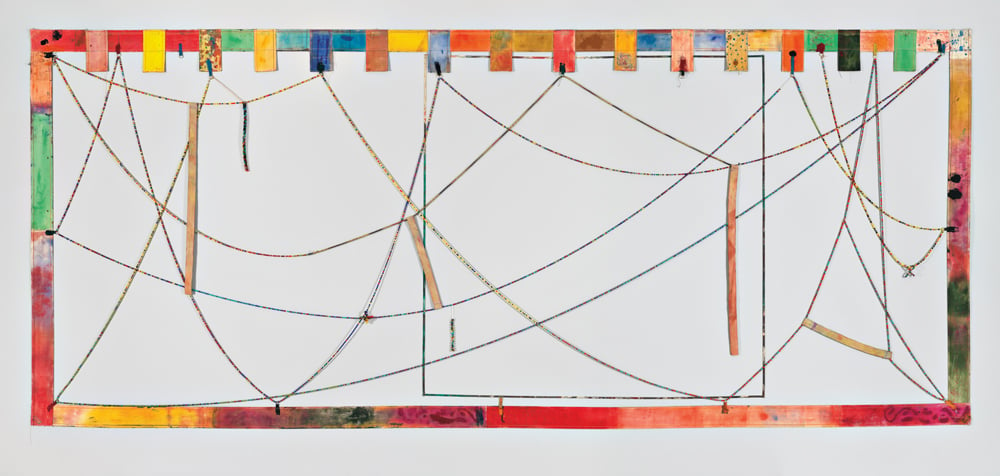

On view at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019, this assemblage by Shields uses acrylic, thread, and beads on canvas to create a work of art tied to countercultural aesthetics of the time from tie-dye to love beads. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art © Estate of Alan Shields

As MoCC’s curator, I installed a George Nakashima Conoid bench front and center, with Wendy Maruyama’s Mickey Mackintosh chair on one side, and a case with Preston Singletary’s Killer Whale Hat alongside Dale Chihuly’s glass baskets based on Native American blankets on the other side. The checklist for the exhibition shared many names and objects with those of Objects: USA and Crafting America. My strategy was to recast the checklist through the exhibition layout, guided by a key question: Whose America is represented in studio craft history?

In terms of craft and national identity, the Craft Revival movement, which ran from the mid-1890s through the 1940s, comes to mind. During this period, missionaries and women’s groups connected social uplift with Arts and Crafts movement philosophies, creating markets for handmade objects from Appalachia in particular, such as baskets, coverlets, and carved wood figures depicting rural life. Craft produced by white Appalachians became known as traditional, erasing both Indigenous and African-American contributions in documented regional history.

Impelled by the Industrial Revolution and readily available factory work, tens of millions of European immigrants arrived on U.S. shores during this time. Industrial and vocational schools were established to teach people how to assimilate and homogenize American life and culture. African-American and Indigenous communities, as well as European immigrants, were taught to build the nation through their labor and hands. Schools remained segregated, and not all communities were taught the same curriculum or given the same job opportunities. In this blanched history of craft in the United States, tradition became equated with handiwork, and national craft heritage with Appalachia.

Haley’s steel sculpture is featured in Crafting America among the works of Robyn Horn, Stoney Lamar, and Michael Peterson. These artists combine elements of abstraction and landscape in their sculptures and material explorations whose form reflects the processes by which they’re made. Courtesy Hoss Haley

So when in 1969 curator Lee Nordness wrote on the back flap of the catalog that accompanied Objects: USA that moving craft “out of folk and into the contemporary” was a goal of the exhibition, that era’s survey of craft at the Smithsonian Institution, he heralded a break from “traditional” Appalachian craft, global folk craft, and the hippie culture of the late 1960s. Instead, Objects: USA was positioned as a celebration of American ingenuity, featuring objects produced primarily by trained artists working with a range of materials via small-scale production.

The project accelerated market demand for modern American craft. But it wasn’t just about selling objects; the exhibition promoted American individualism through craft as it traveled to 22 U.S. museums and 11 European cities over four years. Despite the social turbulence of 1969, only a handful of works in the exhibition engaged in social commentary. In my view, Objects: USA shared a predilection for apolitical work with the marketing of craft through S. C. Johnson and the American Craft Council, much like the promotion of Abstract Expressionism by the U.S. government in the decades prior.

Perhaps thanks to this depoliticization, craft earned a national seal of approval in the 1990s. Amid the culture wars and the struggle to define America that continue today, President George H. W. Bush led Congress to pass Proclamation 6516, establishing 1993 as the Year of American Craft: A Celebration of the Creative Work of the Hand. It was Hillary and Bill Clinton, however, with assistance from Michael Monroe, former director of the Renwick Gallery at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, who created the White House Collection of American Crafts the same year. The collection focused on domestically scaled American studio craft being produced in the 1990s by emerging and established craftspeople, and reflected geographic, ethnic, and aesthetic diversity. The works were chosen to fit in to the White House, which Hillary Clinton described as a home for their family and for the nation.

Designed by Finnish potter Maija Grotell and produced at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1939, this Modernist vase, which was originally featured in the Smithsonian Institution’s 1969 exhibition Objects: USA, is now on view in R & Company’s Objects: USA 2020. Courtesy of R & Company/ Joe Kramm

Ironically, the 1990s were a decade of significant factory-job losses, and this tension between manufacturing and craft, or the machine versus the hand, persists. Where the original Objects: USA celebrated craft as commodity, Objects: USA 2020 reveals process and fabrication, connecting the people, objects, and act of making. This extends, too, into the categories used to describe the people behind the objects: In 1969 Nordness referred to them as “artistcraftsmen,” while in 2020 R & Company used the terms “historical artists” and “contemporary makers.”

Drawn from the Whitney Museum of American Art’s collection, Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019 is one of a number of recent exhibitions at large museums that reframe an institution’s collection through a thematic or relational approach. The curators seem to be guided less by craft than by what historian Jenni Sorkin describes as “Craftlike: The Illusion of Authenticity” in the book Nation Building: Craft and Contemporary American Culture, edited by Nicholas Bell (Bloomsbury, 2015). Sorkin notes there is a great deal of admiration for craft throughout popular culture and contemporary art, but craft’s history is often deliberately overlooked or ignored.

While the questions guiding this exhibition may be new to the Whitney, they are not new to craft. What seems to unite the works in the exhibition is how the artists strategically employ materials and methods. According to the curators, craft’s place in American art is mostly inhabited by women and people of color. Framing the work as marginalized reveals the limitations of an art-historical canon in which hierarchies create tightly contained parameters for what constitutes art—and, in this case, what constitutes Americanness, too. Although Making Knowing boasts a beautifully installed checklist of stunning artwork, the exhibition rehashes old arguments without offering new ways to think about American art, let alone American craft.

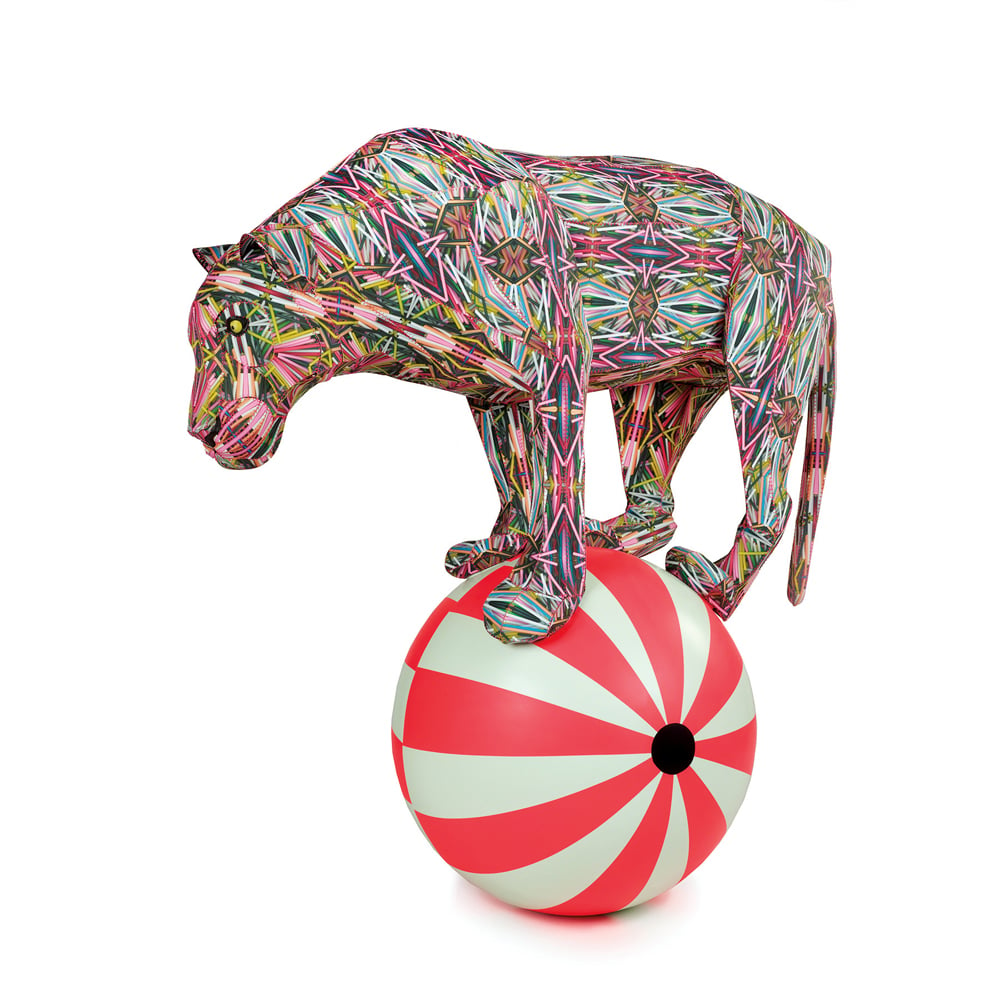

Lemanski’s Tigris T-1 depicts a circus scene with a tiger balancing atop a striped ball. The sculpture is made of cut paper collaged over a hand-built armature. The tiger’s pattern was created by scanning plastic straws that were sourced from an ethnic grocery store near the artist’s studio. Courtesy Steve Mann

By contrast, Crystal Bridges’ Crafting America: Artists and Objects, 1940 to Today takes the Studio Craft movement as its starting point and expands craft beyond its disciplinary classifications of craft under clay, fiber, glass, metal, and wood. The exhibition turns to the Declaration of Independence for its thematic structure, grouping works under the headings of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness: Curators Jen Padgett and Glenn Adamson take common tropes in craft and tie them to these concepts—individualism and legacy are tied to Life; independence and solidarity are framed as Liberty, and pleasure and ingenuity are connected to the Pursuit of Happiness. This curatorial approach feels forced, particularly when some of the craftspeople included are still fighting to be recognized and enjoy the same freedoms as many Americans.

The problems of the framework aside, what Crafting America and Objects: USA 2020 illuminate is that there is a long, well-documented history of studio craft in the United States. Dozens of craft-centric museums and university galleries exhibit and document craft, and have done so for decades. It is time for art history to move past antiquated arguments into the next decade.

This is but one thread in the complex connections between craft and nationalism, and many other questions remain: Which craft? Which America? What needs to be saved? This is where the conversation continues through craft.

Can craft save America? Not through museums alone. The path in the next decade is to demonstrate that multiplicity and Americanness go hand in hand. Craft connects to how we live, how we share, what we make, and it will continue to be a part of how we understand ourselves as individuals. What these projects highlight is a need to make space for more voices; this is where craft will develop in the near future.

You may also enjoy “Three Adaptive Reuse Projects in North Carolina Reinvent Historic Mills”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

The Radical Reshaping of Craft