September 3, 2021

Six Initiatives Model Ways to Practice True Design Justice

Across the globe, architects, designers, and planners are redefining what it means to be an advocate in the design professions.

In June 2020, thousands of people posted a black square to Instagram for #BlackoutTuesday, a social media campaign intended to protest the murder of George Floyd and others in instances of police violence in the United States. The squares took over feeds, eventually “blacking out” valuable news and safety information being shared by Black Lives Matter demonstrators and BIPOC-led mutual aid organizations. In an attempt to advocate for Black lives, Black voices were effectively silenced.

Everywhere you look, this style of performative allyship rears its head. Design professionals are as complicit as any in maintaining structures of oppression.

“People are up in arms and want to organize and be social media advocates, but when the world is opening back up…being present for the struggle of a race that is not your own—or a gender identity that is not your own—is not something [most people] do,” says Taylor Holloway, designer, architect, and core organizer of the collective Design as Protest (DAP).

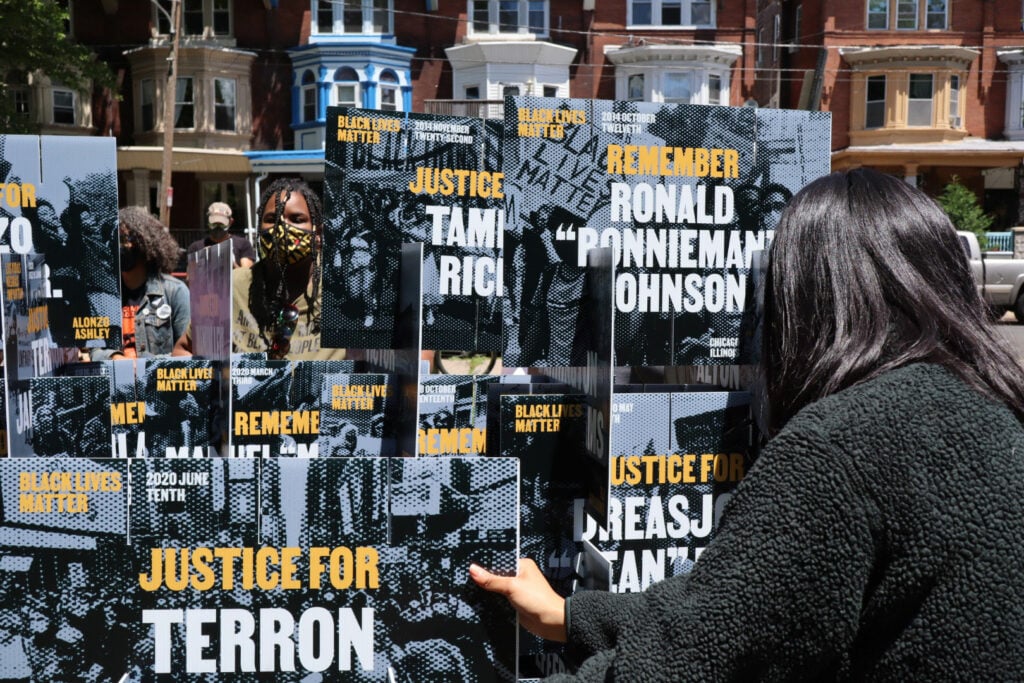

On June 5, 2020, shortly after Floyd’s death, DAP held its first national call with more than 1,000 architects, designers, and engineers who signed on to learn how design justice can inform their practices. During the call, participants discussed a number of demands originally outlined by architect Bryan Lee Jr. in a CityLab article titled “America’s Cities Were Designed to Oppress.” The pronouncements formed the foundation of DAP’s nine Design Justice Demands, which include reducing police funding, abolishing carceral spaces, and restructuring design’s relationship to power, capital, and labor.

“We have over 60 firms that have signed on to the demands,” Lee explains. “What that means is that there are cities and organizations changing their procurement and RFP structures to explicitly engage with parts of the demand.”

DAP is just one of many collectives and initiatives that have emerged or expanded with the intensifying fight for equity in design. All of them show that advocacy isn’t just posting to social media. Advocacy is generosity, empathy, deep listening, and vulnerability. Advocacy is creating infrastructures of care— within oneself and within one’s community.

“Your own uplifting is intrinsically connected to the liberation of someone else,” says Esther Choi, founder of Office Hours, a mentorship initiative for BIPOC design students and emerging art and design creatives. She launched the Zoom-based discussion program as a way to not only help students meet mentors but increase representation within the design community. In addition to Office Hours, the artist and architectural historian has been in support of the efforts of both DAP and Dark Matter University (DMU), an anti-racist design justice network that grew out of DAP’s academic organizing efforts. “I see us all doing different aspects of the same work, but with the same goal,” says Choi.

When it comes to working as a collective, “care and community are central,” says Jennifer Low, landscape architect and organizer at Dark Matter University. Successful organizing is dependent on equality (DAP defines this as having a seat at the table) and equity (having a voice at the table). To establish this, cultivating shared values and establishing community agreements is key—two considerations that are often lost within hierarchical, production-oriented firms. “We are taking an active role in reimagining practice that dismantles the white supremacy rooted in the design community— individualism and the myth of single authorship, ego, and the design hero,” says Low.

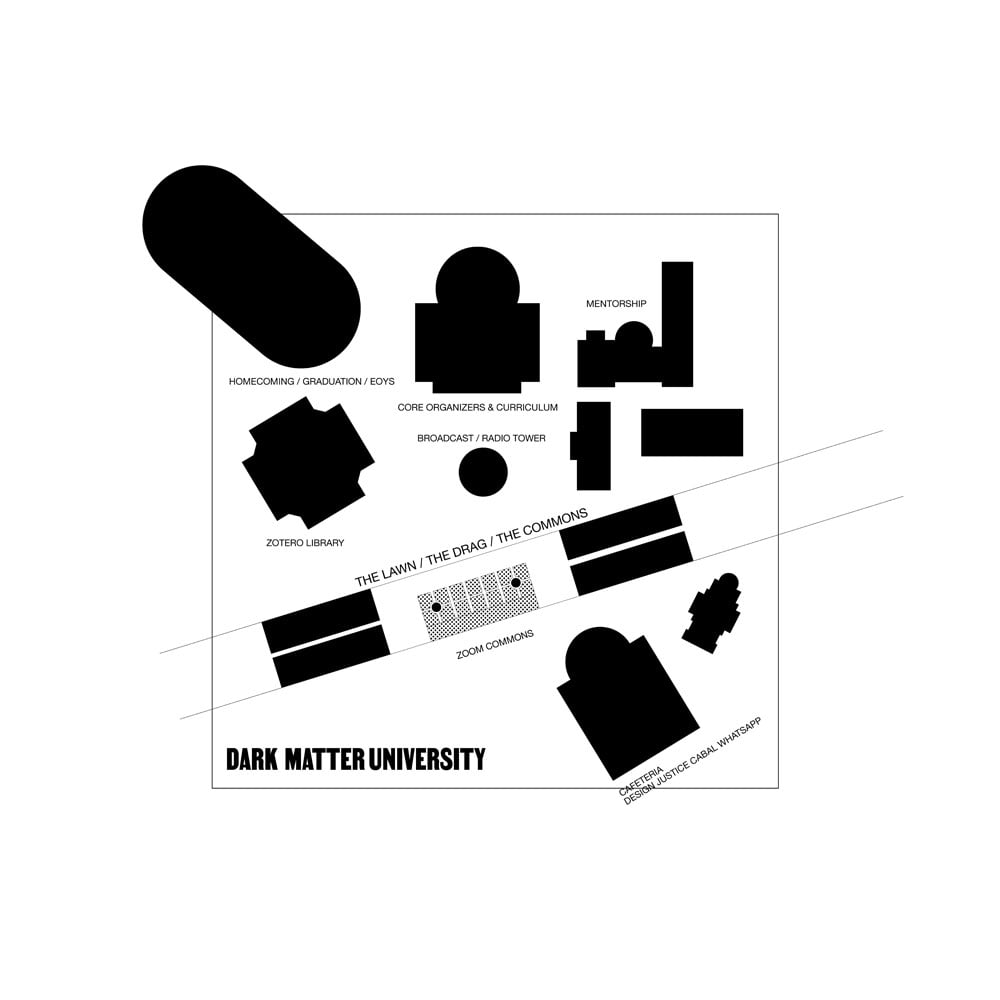

With this in mind, DMU functions as a network of more than 150 educators and organizers who develop anti-racist design curricula for undergraduate students across the United States and Canada in order to “challenge hegemonic pedagogies, canons, and epistemologies.” DMU course offerings are co taught to fairly distribute teaching opportunities, pairing “seasoned educators with less experienced instructors,” explains Low.

By democratizing resources and creating new models of design education, DMU, Office Hours, and DAP all operate as spaces of generosity and mutual care, themes that have also been central to the work of BlackSpace Urbanist Collective since its formation in 2015. Working largely within historically Black neighborhoods, BlackSpace leads design charrettes, manifesto talks, and speculative design workshops that center on Black experience, imagination, and joy.

In their influential book on organizational strategy and facilitation, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, adrienne maree brown asks, “Do you understand that your quality of life and your survival are tied to how authentic and generous the connections are between you and the people and places you live with and in?” The book informed the second line of BlackSpace’s 2019 Manifesto: “Choose critical connections over critical mass. Focus on creating critical and authentic relationships to support mutual adaptation and evolution over time.” By fostering authentic connections among Black urban planners and following ideals of healing and restoration, the collective aims to protect and design the future of Black spaces.

For Design Advocates (DA), collective change is rooted in deep listening. “We learned early in [our] process that there’s a familiar, well-rehearsed approach that architects have in disaster, where they show up and want to communicate their expertise to communities immediately without really listening and understanding,” remarks Michael K. Chen, principal of Michael K Chen Architecture and president of DA.

At the onset of the pandemic, DA formed as a network of architects and designers collecting and sharing data to support small firms navigating lockdown. Recognizing their own relatively secure position and access to resources, DA quickly expanded to form a nonprofit collective that offers pro bono design services to small businesses and organizations in New York City affected by COVID-19. Help ranges from delivering meals to seniors in Chinatown to developing early outdoor parklet dining concepts for restaurants. None of their work could be done without trust building and listening from the very beginning of the design process. “More often than not, we were acting as agents for these businesses that never had direct access to the Department of Transportation or Department of Buildings before,” explains Fauzia Khanani, vice president of DA and organizer at DAP.

To authentically engage with your community means showing up with the awareness that multifaceted identities and perspectives have the power to initiate change. All of these initiatives prioritize the lived experience of those negatively affected by white supremacy, colonialism, and capitalism in order to challenge the few viewpoints that maintain institutional power. Office Hours advocates for the power of self-identification—it’s part of why everyone on the calls is required to turn on their camera as a way to build trust and community, while conveying that this Zoom room is a safe space for students to ask questions and be in dialogue with BIPOC practitioners rather than white mentors. Choi notes, “I have to be mindful that I’m not centering my own experience but providing a fair platform for others.”

When it comes to self-identification, having a sense of humility is key. Straight, cisgender people can’t self-identify as allies, just as white folks can’t simply self-identify as anti-racist. Unlike occupation-based identities, racial and gender identities cannot be turned off. (In other words: There is no such thing as “blue lives.”) Holloway notes how architects and designers in particular tend to conflate their identity with their profession. “They love to talk about how they live their career. But if you’re calling yourself an anti-racist designer, and being a designer infiltrates every aspect of your life, then being an anti-racist individual also needs to permeate every aspect of your work.”

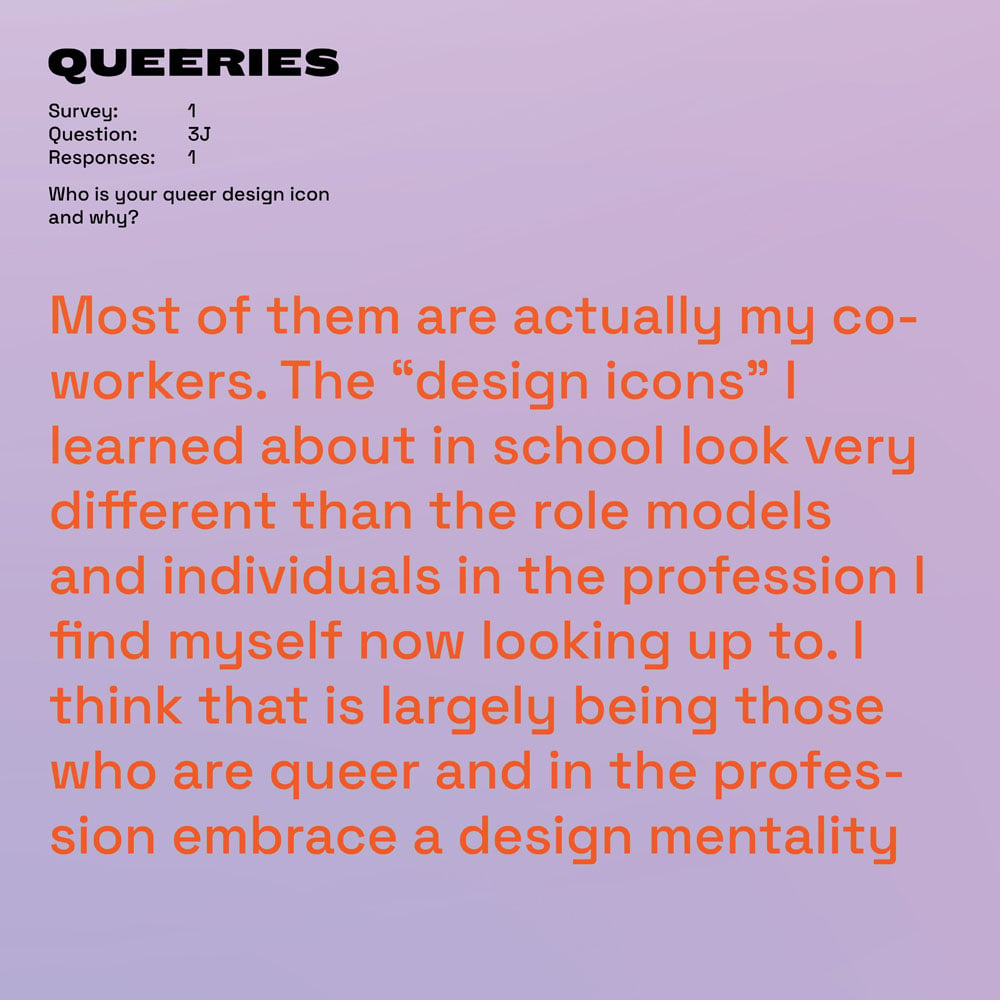

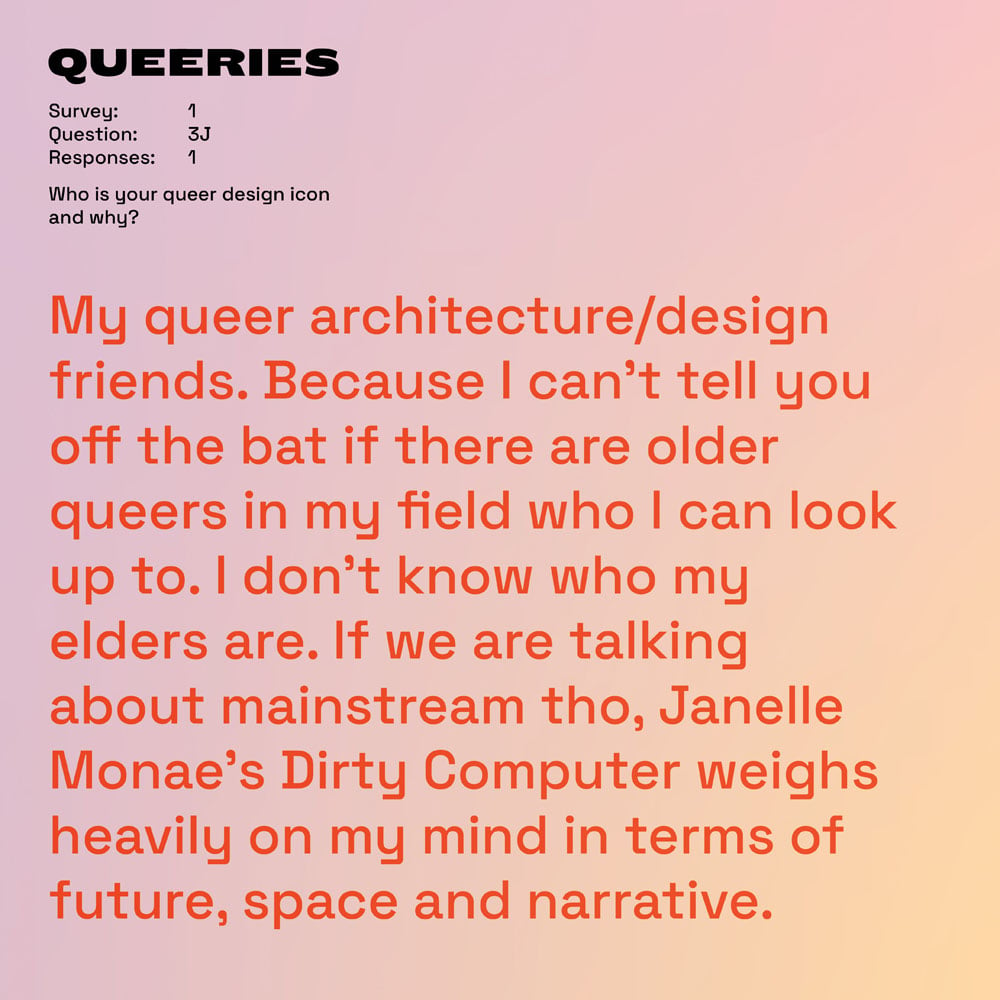

The importance of identity also forms the foundation of Queeries, a series of surveys and discussion groups centered on the lived experience of LGBTQIA+ architects, designers, and students. Launched by architect and organizer A. L. Hu, Queeries explores the intersections of queerness and architecture through storytelling and personal narrative.

“Queerness is a way of life and a different way of thinking,” Hu says. “I think of queerness as a framework through which to look at design and design processes that subvert modes of architecture such as ‘form follows capital.’” Instead, they say, queerness allows designers to focus on what people need and the way spaces can make people feel.

As someone who is also involved in DMU and DAP, Hu believes intersectionality is intrinsic to all the work they do. “Queeries is trying to change the discourse around diversity and inclusion,” they add. “You’ll often get [AIA’s] Women in Architecture off in the corner doing one thing and the National Organization of Minority Architects doing another. There needs to be more of an intersectional approach.”

Intersectional advocacy means acknowledging diverse perspectives and fighting to liberate all. All six initiatives offer clear guidance, tools, and information for shaping a more just design profession. It’s a lot. It’s also just the beginning.

Social impact designer and DAP co-organizer De Nichols notes just how much goes into organizing for design justice, arguing that the cultures of white supremacy and capitalism can be so internalized that they can even cause tension between groups that want the same things. “There’s a lot of nuance to it. But largely, it’s about ‘low ego, high impact,’” she says, quoting a mantra popularized by Kayla Reed, a St. Louis–based organizer and strategist in the Movement for Black Lives. “We put ego aside to link arms with each other for our collective freedom.”

“Your own uplifting is intrinsically connected to the liberation of someone else.”

—Esther Choi, multidisciplinary artist, writer, and founder of Office Hours

“Queerness is a way of life and a different way of thinking. I think of queerness as a framework through which to look at design and design processes that subvert modes of architecture such as ‘form follows capital.’ ”

—A. L. Hu, architect, activist, and founder of Queeries

Design as Protest

Design as Protest is a group of BIPOC architects and designers working to dismantle the “privilege and power structures that use architecture and design as tools of oppression.” As part of a fundraising effort that marks the celebration of its one-year anniversary, DAP recently launched a newspaper that includes its Anti-Racist Design Justice Index (ARDJI), an in-depth matrix that serves as a “living tool” for professionals committed to “taking action against systemic racism within design practices, organizations, academic institutions, and local governments.” The ARDJI lists concrete actions (Acknowledgement, Accountability, Representation, Reparations, Accessibility, and Influence) in four different directions (Equality, Equity, Justice, and Liberation) that cover areas such as finance, leadership, labor, curriculum, methodology, budgets, planning, and development.

DESIGN AS PROTEST DESIGN JUSTICE DEMANDS

- Divest & Reallocate Police Funding

- Cease the Implementation of Hostile Architecture & Landscapes

- Abolish Carceral Spaces

- Restructure Design’s Relationship to Power, Capital & Our Labor

- Center Community Leadership in Design & Planning Processes

- Create, Protect & Reclaim Public Space Through Liberatory Planning & Policy

- Cultivate Anti-Racist Visions for Affordable & Just Neighborhoods

- Preserve and Invest in Black, Brown, Indigenous & Asian Cultural Spaces

- Create Anti-Racist Models of Design Education, Training & Licensing Challenge Power. Dismantle Systems.

- Design a Just World.

Office Hours

Formed in the summer of 2020, Office Hours is an initiative created by multidisciplinary artist and architectural historian Esther Choi. Prompted by requests for professional advice she received from young BIPOC creatives, Choi broadcasted on her Instagram Zoom talks steps for applying to PhD programs. Recognizing the absence of people of color in the A&D professions and of adequate mentorship opportunities for BIPOC students, Office Hours emerged. Practitioners now offer weekly 75-minute discussions and Q&As on their professional journeys. The program is sponsored by the Architectural League of New York.

OFFICE HOURS’ GOALS ARE ROOTED IN INTERSECTIONAL JUSTICE AND EQUITY.

- Increase representation Office Hours aspires to highlight a diverse range of cutting-edge BIPOC creatives in the fields of architecture and design visible to younger audiences. Being seen is important. We believe that self-identification is crucial to forming the belief that being a BIPOC creative is possible.

- Increase access to knowledge We seek to provide free information and professional advice for BIPOC creative practitioners in an intimate format to encourage self-determination. Embracing intersectionality, we encourage our speakers to engage in open discussions about the ways that their individual, overlapping social identities have shaped their professional experiences and insights.

COMMUNITY AGREEMENTS

We ask our participants to do their part in fostering a positive and uplifting environment by being:

- Inclusive of people of every race, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, ethnicity, nationality, disability, religion, age, physical appearance and body size, language, immigration status, and economic status.

- Accountable to the community by showing up as an active participant, rather than remaining anonymous. We ask all community members to turn their cameras on for our online discussions* to ensure that our programming is reaching the people it’s intended for.

- Intentional with your words by refraining from offensive or aggressive language, hate speech, or abuse of chat functions.

- Mindful of the impact of your words and actions on others.

- Respectful of guest speakers, moderators, and audience members by refraining from sustained disruption during events.

- Conscious of other people’s personal space and boundaries.

- Although we do not gather physically in the same space, we recognize that histories of settler colonialism mark the lands on which we work and live. We are committed to supporting Indigenous rights and are grateful for all that these lands have provided.

* If you have a disability preventing you from participating on screen or would benefit from additional support such as an ASL interpreter at Office Hours events, we encourage you to please email us at [email protected] in advance. If technological limitations or other reasons prevent you from engaging fully, let us know, too. As we grow this initiative, we hope to support more inclusive and accessible forms of participation.

* If you witness or experience inappropriate conduct during an Office Hours event, please alert us ASAP by sending an email to [email protected]

Dark Matter University

Dark Matter University (DMU) is an anti-racist design justice school formed on July 1, 2020. Led by a core group of 30 design educators across the United States and Canada, DMU also encompasses a roster of over 161 organizers who have developed numerous courses through partnerships with Howard University, Tuskegee University, and the University of Michigan, among other institutions.

“We are trying to be a part of the change we want to see, from having an all-BIPOC lineup of speakers and educators, to modeling a collaborative, nonhierarchical form of curriculum development and education, to challenging toxic studio culture,” says DMU educator and artist Chat Travieso.

DMU MISSION

Dark Matter University is a democratic network with the following principles guiding its actions.

We Work to Create:

- New Forms of Knowledge and Knowledge Production through radical anti-racist forms of communal knowledge and spatial practice that are grounded in lived experience. We challenge hegemonic pedagogies, canons, and epistemologies drawn from paradigms of white domination while elevating ancestral and local knowledge.

- New Forms of Institutions along a networked resource distribution model between institutions. We extract from those who have extracted to collate resources and lift up marginalized voices.

- New Forms of Collectivity and Practice that democratize models of practice, education, and labor at all phases of production. We operate with deep consideration of ethics and a duty of care, moving from hard to soft power.

- New Forms of Community and Culture that expand the circle of those contributing to anti-racist design pedagogy and practice. We actively build power and share knowledge to build capacity and resilience in communities beyond the preconceived boundaries of our fields.

- New Forms oof Design that open the possibilities and methodologies for designing the built environment. We aim to co-create new formal and spatial imaginaries that serve broader, often overlooked, constituencies and consider multiple subjectivities.

BlackSpace Urbanist Collective

BlackSpace is a collective of more than 200 Black urbanists, architects, designers, and artists. Formed in 2015, BlackSpace uses a manifesto-based strategy for bringing resources such as design education, workshops, exhibitions, and celebrations into historically Black neighborhoods. During 2020, the collective’s national affiliate groups “expanded focus on reclaiming Black safety in public space,” explains Emma Osore, co-managing director, BlackSpace. Building off their manifesto’s call to “Celebrate, Catalyze, and Amplify Black Joy,” BlackSpace facilitated events such as drive-in movies in Oklahoma City’s historically Black Deep Deuce District, Black-owned business tours in Chicago, and outdoor roller-skating pop-ups honoring Indianapolis’s Black recreation heritage.

THE BLACKSPACE MANIFESTO

We are Black urban planners, architects, artists, activists, and designers working to protect and create Black spaces. Our work includes a range of activities from engagement in historically Black neighborhoods to hosting cross-disciplinary convenings and events. While what we do is very important, the way we do it is also critical. Acknowledging our past oppressions, triumphs, future aspirations, and challenges, we’ve created this manifesto to guide our growth as a group and our interactions with partners and communities. We push ourselves, our partners, and our work closer to these ideals so we may realize a future where Black people, Black spaces, and Black culture matter and thrive.

- Create Circles, Not Lines Create less hierarchy and more dialogue, inclusion, and empowerment.

- Choose Critical Connections Over Critical Mass Quality over quantity. Focus on creating critical and authentic relationships to support mutual adaptation and evolution over time.

- Move at the Speed of Trust Grow trust and move together with fluidity at whatever speed is necessary.

- Be Humble Learners Who Practice Deep Listening Listen deeply and approach the work with an attitude towards learning, without assumptions and predetermined solutions. Take criticism without dispute.

- Celebrate, Catalyze, and Amplify Black Joy Black joy is a radical act. Give due space to joy, laughter, humor, and gratitude.

- Pland With, Design With Walk with people as they imagine and realize their own futures. Be connectors, conveners, and collaborators— not representatives.

- Center Lived Experience Lived experience is an important expertise; Center it so it can be a guide and touchstone of all work.

- Seek People at the Margins Acknowledge the structures that create, maintain, and uphold inequity. Learn and practice new ways of intentionally making space for marginalized voices, stories, and bodies.

- Reckon With the Past to Build the Future Meaningfully acknowledge the histories, injustice, innovations, and victories of spaces and places before new work begins. Reckon with the past as a means of healing, building trust, and deepening understanding of self and others.

- Protect & Strengthen Culture Make visible and strengthen Black cultures and spaces to honor their sacredness and prevent their erasure. Amplify and support Black assets of all forms—from leaders, institutions, and businesses to arts, culture, and histories.

- Cultivate Wealth Cultivate a wealth of time, talent, and treasure that provide the freedom to risk, fail, learn, and grow.

- Foster Personal & Communal Evolution Make opportunities to expand leadership and capacity.

- Promote Excellence Amplify, elevate, and love Black vanguards and the variety of their challenging, creative, exceptional, and innovative work and spaces. Allow excellence to build influence that creates opportunities for present and future generations.

- Manifest the Future Black people, Black culture, and Black spaces exist in the future! Imagine and design the future into existence now, working inside and outside of social and political systems.

Design Advocates

Design Advocates (DA) is a nonprofit network of architects, designers, and advising firms that collaborate on research and projects for small businesses and organizations in New York City. Founded in April 2020 as a platform for collecting data and empowering design businesses affected by COVID-19, the group has since expanded to push for mutual advocacy and equitable design more permanently.

DA’s pro bono “Test Fits” initiative was launched to help local restaurants and small businesses respond to the crisis and ensure safe operations. DA has also assisted social service organizations such as the Bowery Residents’ Committee and Housing Works as well as the Greater Harlem Chamber of Commerce and a number of public schools.

DESIGN ADVOCATES BOARD OF DIRECTORS:

- Michael K. Chen, MKCA, President

- Fauzia Khanani, Studio Fōr, Vice President

- Abigail Coover, Overlay Office, Secretary

- Jane Lea, Lea Architecture, Treasurer

- Nicholas McDermott, Future Expansion, Director

- Michael Yarinsky, Office of Tangible Space, Director

PARTICIPATING FIRMS:

- Abruzzo Bodziak Architects

- Architensions

- Barker Associates Architecture Office

- BRANDT : HAFERD

- Bureau V

- BÜRO KORAY DUMAN

- Carolynn Karp Design

- Cedar Street Creative

- Davies Toews Architecture

- Drawing Agency

- Facility Systems

- Fitchwork

- Future Expansion Architects

- Frederick Tang Architecture

- Gleicher DesignHWKN

- Hye-Young Chung Architecture

- Kalos Eidos

- KSD Architects

- Ladies & Gentlemen Studio

- Lea Architecture*

- Meyer Design

- Michael K Chen Architecture*

- New Affiliates

- Office of Architecture

- Office of Tangible Space*

- Office of Things

- Only If

- Overlay Office*

- Palmyra

- Parc Office

- Pliskin Architecture

- Primary Projects

- Project AZ

- Restless Works

- Scalar Architecture PC

- Smith & Sauer Architecture

- SomePeople

- Space4Architecture (S4A)

- Space Ctrl Design

- SpaceODT

- Studio 2x

- Studio Cadena

- Studio Fōr *

- Studio Modh Architecture

- Studio Lyon Szot

- Ten to One

- The Seed

- W.I.P.

- Worrell Yeung *

- Zaidi Christo Design

*Founder

PARTNERSHIPS:

- NYC Economic Development

- CorporationAIANY/The Center for Architecture

- Neighborhoods Now

- Van Alen Institute

- Urban Design Forum

- NYCxDESIGN

Queeries

Founded on the premise that identity has the power to shape design, Queeries is an ongoing survey of LGBTQIA+ architects, designers, and students exploring the intersections of queerness and architecture. The poll documents the multifaceted experiences of queer designers in both workplace and academic settings. Responses are used for community discussions and are distributed on Instagram and in the newsletter Queer Agenda. The survey and newsletter are the brainchild of A. L. Hu, a queer, trans, nonbinary Taiwanese- American architect, organizer, and facilitator based in New York City. Hu is currently the design initiatives manager at the nonprofit Ascendant Neighborhood Development and co-organizes with both Design as Protest and Dark Matter University.

WHY QUEERIES? WHY NOW?

Identities are political. How one identifies and how one is perceived by others can affect design philosophies, processes, and outcomes. Quantifying and qualifying the multifaceted experiences, stories, and feelings of queer designers confronts discourses of diversity, equity, and inclusion within design professions. As LGBTQIA+ issues and queer spaces become increasingly important, engagement with and community-building among queer architects and designers is vital to ensure the inclusion of our voices. Communities of queer architects and designers exist in isolated pockets around the U.S. The responses collected through Queeries serves as documentation of our existence—a living history of sorts—despite the lack of queer representation in current surveys and demographic studies.

Latest

Projects

5 Buildings that Pushed Sustainable Design Forward in 2022

These schools and office buildings raised the bar for low-carbon design, employing strategies such as mass-timber construction, passive ventilation, and onsite renewable energy generation.

Projects

The Royal Park Canvas Hotel Pushes the Limits of Mass Timber

Mitsubishi Jisho Design has introduced a hybrid concrete and timber hotel to downtown Hokkaido.

Profiles

Meet the 4 New Design Talents Who Made a Mark This Year

From product design to landscape architecture and everything in between, these were the up-and-coming design practices making a splash in 2022.