November 3, 2022

The Dark Side of Rick Caruso’s Fantasy Worlds

Caruso’s architecture—and his urban impact—has almost always represented a move backward, away from the modern, dynamic city.

Sam Lubell

Say what you will about Los Angeles mayoral candidate Rick Caruso, and his politics, his buildings say something too; and they deliver a mixed message. The developer-cum-politician’s projects have stamped a very particular imprint onto Southern California. On one hand, most are clean, pleasant, well-made, walkable, and wildly popular places, transforming neighborhoods and fostering community in locales that are often been bereft of it. On the other hand, their faux, retro banality has helped shift the region’s tastes backward, fueled a rash of bad historical building, and spurred gentrification, elitism, and a culture of homogeneity, manipulation, and surveillance.

A developer since 1990, Caruso launched his career by building high-end Mediterranean-themed shopping centers with red tile roofs, loggia, gazebos, generous archways, and the occasional belltower, like Encino Marketplace (1994), The Village at Moorpark (1996), The Promenade in Westlake (1996), and The Commons at Calabasas (1998). Each is a much nicer place to go than the average shopping plaza. But as with Caruso’s entire portfolio, you feel a little bad enjoying them. Like you’re selling your soul to the ingeniously seductive sirens of corporate America. (Each, by the way, is located in a predominantly white part of a region that is anything but.)

Caruso came into his own with The Grove, the 2003 open air retail and entertainment center designed by a team led by Elkus Manfredi that married the eclectic, quaint, and manufactured historicism of Disneyland—there’s a main street, and, of course, a trolly—with a frenzy for in-person shopping that now seems equally quaint. The main street is quite walkable, informed by a manicured, carefully designed sequence of well-detailed buildings (styles include Colonial, Italianate, and even Art Deco, but nothing more modern than that), wide sidewalks, water, greenery, a town square, fountains, kiosks, marquees, and anchors like the Farmers Market (by far the most authentic establishment on the premises) and a green-domed Nike store.

Right off the bat The Grove was a huge hit, registering more visitors than its role model, Disneyland. Its sales per square foot consistently rank in the top three retail outlets in the country. Such success begat equally-eclectic-but-not-quite-as-impressive imitations like The Lakes at Thousand Oaks (2005), which, to its credit, inserted parkland into the mix of the usual outdoor shopping experience; The Americana at Brand (2008), centered around a lake, a townscape, and the concept of living in faux-historic luxury; and upscale urban revamps like Waterside at Marina Del Rey (2005) and Palisades Village (2018.) In recent years Caruso has embraced a slightly more varied—and to his credit, more connected to the city—approach, reflecting trends like industrial warehouse-chic (252 S. Brand), the adaptive reuse of historic structures (The Masonic Temple), and even glassy, earnestly futuristic (but kind of awkward) neo modern residences (8500 Burton).

But while Caruso has veered into some new territory, his bread-and-butter has always been the historical, the precious, the Disney-esque. Caruso, not surprisingly, idolizes Walt Disney, but he doesn’t seem to possess the future-looking side that drove Walt. (Have you ever seen Walt’s original plan for EPCOT?) While Caruso has been an effective innovator in the world of retail development, his architecture—and his urban impact—has almost always represented a move backward; away from the modern, dynamic city. Back to a more manageable, simpler time; to a more homogeneous age—or an assemblage of ages—when things were, at least many think, “better.”

The skillful placemaking of Caruso’s work has helped propel Southern California retail out of the age of the mall and into that of the outdoor lifestyle experience. Many love visiting his creations, which have created town centers, pedestrian bustle, green space, and meet-up opportunities in neighborhoods that glaringly lack them. Several offer live entertainment, pop-ups, holiday lighting, and other effective activations. That civic value is real. But the nostalgia and luxurious sheen baked into most of Caruso’s projects has a darker side that is not civic at all. It’s about a manufactured yearning for an unattainable time, place, and lifestyle. It’s an aspirational, culturally regressive nostalgia.

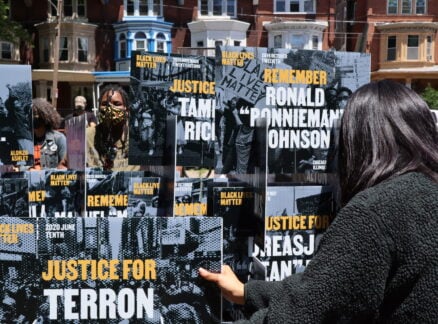

While each of Caruso’s developments is expertly made, and can be enjoyable for a quick trip, the reason many of us start to feel a little nauseous spending a lot of time in them (kind of like spending too much time in Las Vegas) is that they are simulacra, facades. They are not based in their contexts, and they are not designed as true urban places. They are often separated from their surroundings, requiring implied payment (through parking and shopping), sucking the life from the real main streets around them, not offering enough affordable shopping (or in some cases housing), and driving up costs for less wealthy residents nearby. They rarely include local retailers (At The Grove, the pre-existing Farmers Market, with its L.A.-based vendors, contrasts starkly with Caruso’s upscale, omnipresent global brands like Sephora, Nike, Diptyque, and Nordstrom) or allow for the organic, piecemeal change, chaotic streetlife, or spontaneous urban activities that real cities do. (Just last month, for instance, a judge ordered that opponents of Caruso’s campaign could finally protest at The Grove.) And they could be inserted virtually anywhere. They may appear civic, but they are not. Their target demographic is not the general public; it’s those who can afford to pay high prices for top-shelf items or luxury living. Which is a fine goal for a developer, perhaps, but not for someone with aspirations to improve everyone’s civic life.

While the work of Caruso’s design team is far better, his brand of aspirational nostalgia is the same employed by the notorious developer Geoff Palmer (of The Medici, Orsini, Visconti, etc.) and the many others who have driven what The Urbanist called L.A.’s “Fauxtalian Renaissance,” and it shares the same manipulative, elitist spirit that has spilled into many new large-scale developments in the city, from Playa Vista to Hollywood to Downtown. Glassy, contemporary developments can be just as placeless, and just as cunning in pretending to put the welfare of their neighborhoods above profits. It’s an opportunistic, cynical, anti-civic approach that many of today’s politicians—including fellow developer Trump—employ; fueled by the public’s desire to disengage with the challenging messiness of modern urban life. A desire for simplicity, luxury, sameness, cleanliness, order, control, and fantasy; for everything that a city, and a democracy, is not about. Politics are politics, and every politician has a past. A million factors go into what makes a candidate effective. But don’t ignore what Rick Caruso has produced in his “other” career.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

5 Buildings that Pushed Sustainable Design Forward in 2022

These schools and office buildings raised the bar for low-carbon design, employing strategies such as mass-timber construction, passive ventilation, and onsite renewable energy generation.

Projects

The Royal Park Canvas Hotel Pushes the Limits of Mass Timber

Mitsubishi Jisho Design has introduced a hybrid concrete and timber hotel to downtown Hokkaido.

Profiles

Meet the 4 New Design Talents Who Made a Mark This Year

From product design to landscape architecture and everything in between, these were the up-and-coming design practices making a splash in 2022.