November 11, 2022

Reality Keeps Catching Up with N.K. Jemisin

Now, with the release of its sequel The World We Made, Jemisin concludes a story into which the real world cannot help but intrude. Originally set to feature a demagogic president who used the city to further a rightwing political agenda, Jemisin found her plot preempted by the election of Donald Trump. Other challenges from the pandemic emerged, especially as she was constrained from visiting real-life locations like the Gracie Mansion, home to the city’s mayor, to add the kind of detail she sought out.

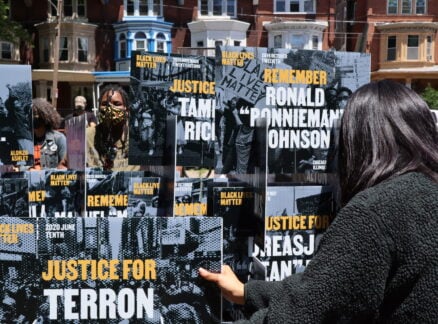

Nevertheless, The World We Made remains a satisfying conclusion to the project, full of the same sense of city-ness that made its predecessor so gripping. From grappling with Staten Island’s uneasy relationship to the other boroughs, to witnessing how Ry’leih, the alien force, uses gentrification and white supremacy to destroy the city, Jemisin spins recognizable social phenomenon into dizzying and daring speculative fiction.

Metropolis caught up with Jemisin about how the book was transformed by the ever-evolving events of the last few years, how gentrification is erasing the fundamental spirit of the city, and how everyday New Yorkers have continued to fight back against countless adversities in recent years.

Annie Howard: As you suggest in the acknowledgements of The World We Made; the shape of this work changed dramatically from when you started it. What was it like to see reality transform this imaginary version of the city you were creating?

N.K. Jemisin: The original plot would have involved the newly awakened New York fighting against a demagogue president who decided to attack the city in order to advance his own political agenda, and then Trump did that, and I was like, ‘I’m not taking inspiration from this motherfucker,’ pardon my language. I’m not going to let him steal my plot, and I had to change the story completely.

That was also what contributed to me being frustrated with the series, because the things that I thought of as fantastical kept happening. Imagine the ridiculousness of this moment: This was supposed to be a lighthearted, by my standards, examination of human interaction with cities, focusing on the romance of a person’s interaction with their city. But every time I turned around, I saw the city transform literally as I was working on it.

I was trying to capture the character of the city at a time when the character of the city was just in massive flux, and I couldn’t keep up. I originally wanted to include elements of Gracie Mansion in the story, because as you see in the second book, it was all about the mayoral campaign. I was going to go farther into Brooklyn’s actual first 100 days as mayor, and I was going to have this subplot with Gracie Mansion, but I couldn’t go and visit Gracie Mansion because of the shutdown. I’ve half-jokingly, half-seriously said that I don’t know if I’m going to be writing any more stuff in the real world, because it’s just too hard to keep up.

AH: In the book, as in real life, the character of Staten Island, known as Aislyn in her human form, has a complicated relationship with the rest of the city. What did you hope to capture in narrating her relationship to the rest of the city?

NKJ: I did not want to give her a redemption arc. Redemption requires repentance and a desire to be better and do different things, and she wasn’t there and might not have ever gotten there. Xenophobia is a quintessential part of her character because that is part of Staten Island. Still, Staten Island will pull up and fight for the rest of New York instantly when somebody insults it, but most of the time it’s a sibling relationship: You hate them, you fight them, but if somebody messes with them, you are right there, ready to throw down. Staten Island is a valuable part of New York City, as much as the rest of the boroughs, but it’s just a such a drastically different character that you do have to treat that as an adversarial relationship. What I did was to say: we don’t have to like each other, but we must have a workable relationship.

AH: As you acknowledge when writing about Manny, the embodiment of Manhattan, so many parts of that borough have been filled with luxury-built, unoccupied housing for years that parts of the city are essentially offline. What’s it like to see New York continue to be remade so thoroughly by real estate?

NKJ: I am seeing the pace of gentrification pick up, and I’m seeing it develop elements that disturb me. It used to be that gentrification was driven primarily by small, local real estate firms, but what I’m seeing now is large corporations come and buy up pieces of the city that were still affordable and deliberately driving up prices. I’m doing well enough that I could buy a condo, but up until my book The Fifth Season blew up, I had no expectation of ever buying a piece of the city.

We’re losing so much as a result. It’s not just people, it’s that art nouveau character to the city. We no longer get those beautiful buildings being made, it’s just this generic, prefab housing, and they all look the same, these glass and steel monstrosities. We’re seeing the character of the city slowly whittled away, and I do not think the New York that I loved and wrote about in the first book, I don’t think it exists anymore as the second book, let alone a few years in the future. I hope that I’m wrong, but I’ve seen the pace accelerate and reach a point of no return. But I suppose we’ll see what happens.

AH: Like the rest of the world, New York has been tested in recent years, and we’re still witnessing things continue to change in the wake of the pandemic. What’s it been like to live in the city in this time, especially as you write this fantastical representation of the city and its peoples?

NKJ: As I was studying the city, to the degree that I could without physically going out and visiting places, I was impressed with the realization that New York is fighting back. On every street, every block, something is happening. My half-dead block association roared back to life and began protesting the instant that the city started using targeted sidewalk citations—[minor infractions against property owners responsible for upkeep of public property like sidewalks]—to create liens against houses in the area. For me, that’s New York.

For a very brief while after 9/11, when the city was partially shut down, New Yorkers looked out for each other. There’s that quintessential image in New York, which is that whenever there’s a power outage, citizens jump into the street and start directing traffic. There aren’t enough cops to kind of manage everything at that point, and ordinary people start doing it, because otherwise the city can’t function. Somebody’s got to do it, somebody must step up and do the work. There’s always someone who does that.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

5 Buildings that Pushed Sustainable Design Forward in 2022

These schools and office buildings raised the bar for low-carbon design, employing strategies such as mass-timber construction, passive ventilation, and onsite renewable energy generation.

Projects

The Royal Park Canvas Hotel Pushes the Limits of Mass Timber

Mitsubishi Jisho Design has introduced a hybrid concrete and timber hotel to downtown Hokkaido.

Profiles

Meet the 4 New Design Talents Who Made a Mark This Year

From product design to landscape architecture and everything in between, these were the up-and-coming design practices making a splash in 2022.